︎Kusama, spotted︎

Hindley Wang

Feb. 2023

(the published version is here, the original text in bold)

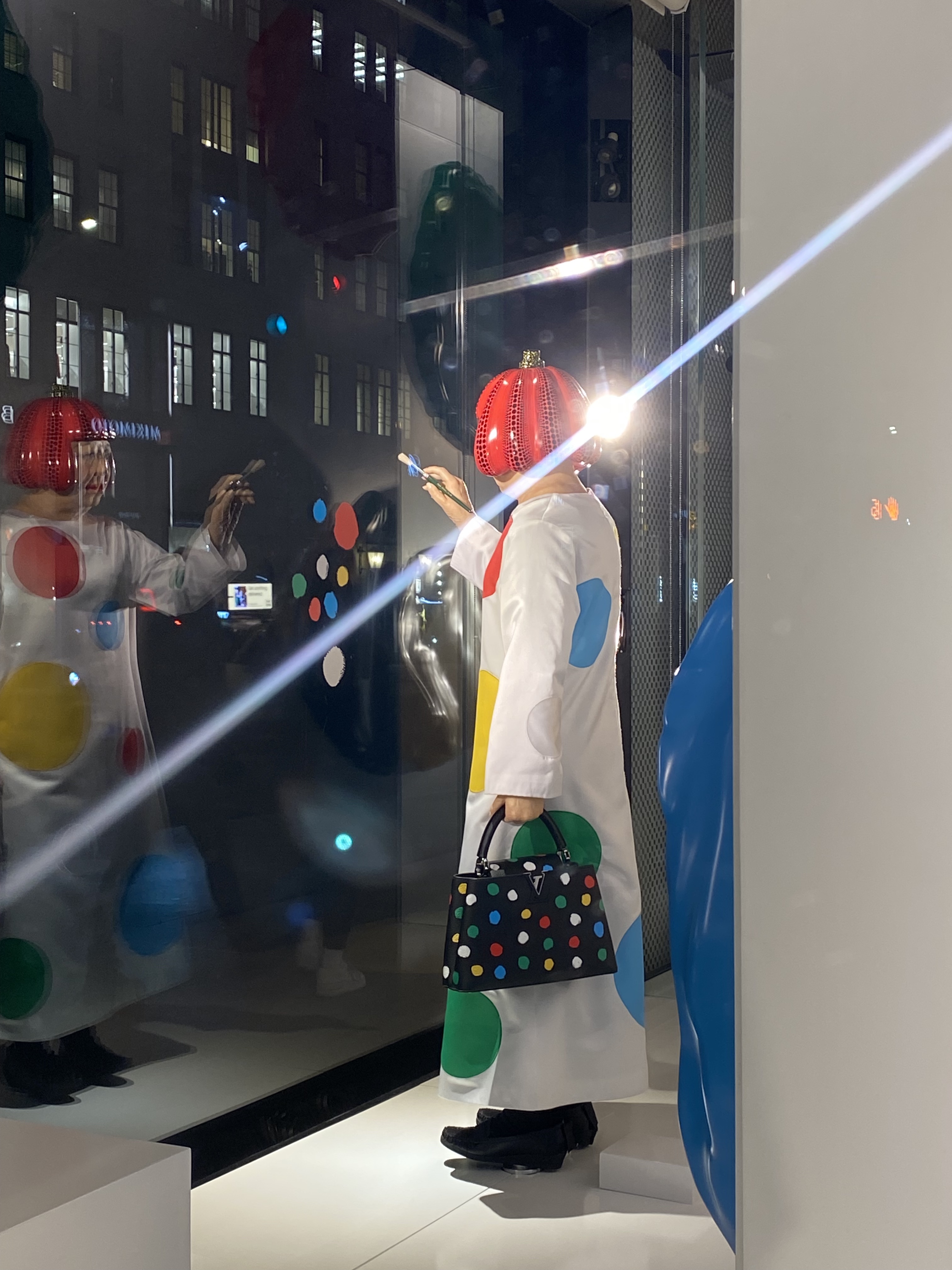

Spotted, this side of the 5th Ave is dotted with “paint”: massive stickers of paint blobs realistically rendered in artist’s brushstrokes, adorn the sidewalk, touching the feet of everyone that comes to pass. Earlier this month, Louis Vuitton launched its new rounds of global campaigns in collaboration with the artist Yayoi Kusama. The insulated box of mirrored infinity that had people lined up on the street all over the world now finds its way to reclaim the street.

“Is she alive?”

“Wow, she is smiling at me…Hi!!”

I too found myself drawn to the color dotted side of the 5th Ave. I searched for my phone, on sight of the uncanny dots and the many spectators, feeling slightly insecure about the fact that I did not already have it in hand. I zoomed in towards the window frame, caught by the wrinkles on her face, under the red, acrylic, shiny, polka-dotted pumpkin helmet, and observed her pouchy eyelids weighing on that signature (in)expression of skepticism: the rounded stare imbued with a hint of obsession that is irreducible even to its robotic facsimile. I waited for it to turn, to me.

And finally, in slow motion and blinks of several eyes, she turned her robotic stare on me. In that split second where “her” gaze met mine, the certitude from her sharpened pupils captured me in a sinking disquietude: what am I looking at? The artist, the robot, a thing, or a person? And perhaps, more dauntingly: what was she/it looking at?

Before I dive deep into the discomfort, let us actually take a look at the shop window, to reanimate the spatiality of the scene.

Against a rather plain backdrop, “Kusama” attends to what is in front of her, the eight colored dots on the shop window, looking over “us”. Gesturing with a clean brush in her right hand, she points to the different dots, and “paints”, suggestively, while her left arm faithfully clings onto the artifice: a Louis Vuitton and Yayoi Kusama edition of the Capucine Bag, in black.

Gesturing with a clean brush in her right hand, she points to the different dots, and “paints”, suggestively;

while her left arm faithfully clings onto the artifice: a Louis Vuitton and Yayoi Kusama edition of the Capucine Bag, in black.

while her left arm faithfully clings onto the artifice: a Louis Vuitton and Yayoi Kusama edition of the Capucine Bag, in black.The concept of “paint”, in the self-contained shape of the “dot”, undergoes several kinds of rematerialization. Painted dots are selectively splattered on the white backdrop behind the automaton, turning what used to be a medium of expression into an ornamental artifice, clenching onto the wall like bad batter or dried gum. A similar ornamental logic is reflected on the “body” as well: plain white dress of a synthetic fabric, devoid of any sign of craftsmanship, sewed with patches of colored circles, corresponding to the organizing principle that surrounds and confines.

Here we have it, the three physical interfaces of the display, crossing over pictorial, sculptural, spatial and tactile registers.

Known for her psychedelic infinity mirror rooms and hallucinatory polka dots on everyday objects, this Kusma robot stands alone, in a rather bare state, like a beginning.

The context of creation is stripped bare. The oeuvre is laid plain.

Scene from Yayoi Kusama, Self-Obliteration, 1967.

In 1967, Kusama performed her (in)famous Self-Obliteration. In the film, Kusama begins by covering herself and a brown horse with white dots, extending to the various surfaces of the tangible world: surfaces of hair, of skin, of water, of tree, and ultimately with the cinematographic help of Jud Yalkut, of light itself, the very medium of optical perception. The performance crescendos as the whole world becomes a camouflage in spite of itself. An eradication of the “whole”, by unifying the parts, in the creation of the infinite.

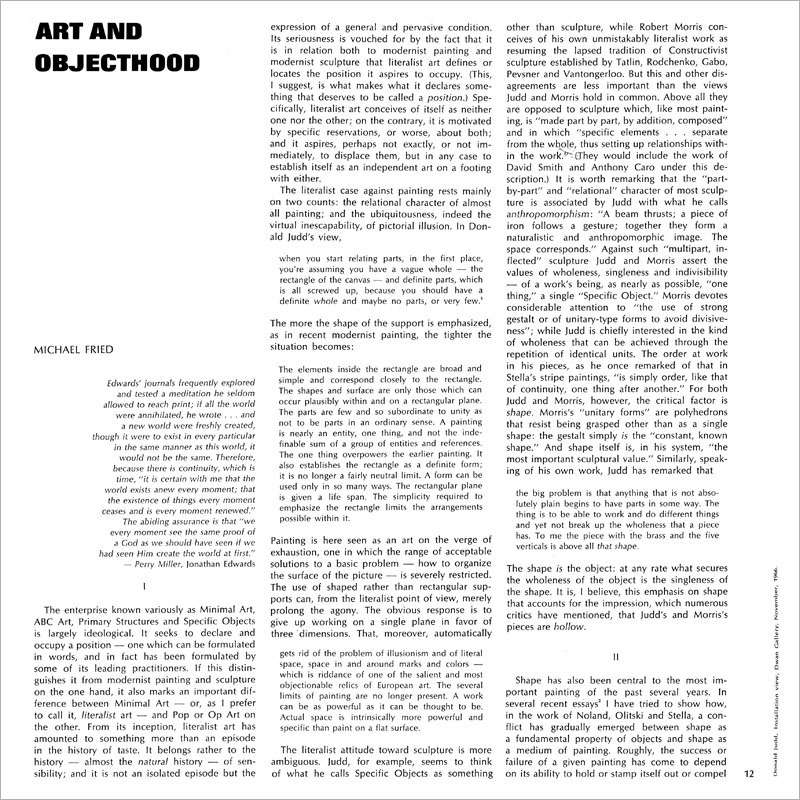

Artforum Print Summer 1967.

Robert Morris, Untitled, 1965.

The same year in New York, Micheal Fried published his canonical critique, “Art and Objecthood”. While “art” has since marched on into the arms of “theatricality”, Fried’s discontent with the anthropomorphic objecthood of Minimal art invokes a compelling tension still present in the scene before me. For him, the essence of modern art is a solitary existence on its own. In contrast, Minimal Art with its theatrical mode of display presupposes the possession of a beholder, “for theater has an audience—it exists for one—in a way the other arts do not.” Specifically, Fried diagnosed in theatrical art the need for “the beholder’s body” to complete the experience of the situation. In the essay’s most breathtaking leap of logic, the perceived “hollowness” of minimalist cubes becomes for Fried a telltale sign of their anthropomorphism, a theatrical quality he conflates with the literal “objecthood” of both artworks and human bodies.

Although in no way am I proposing any likeness of the shop display to Minimal Art, the effect of theatricality in the shop window does urge reconsideration of the intersection of objecthood and the beholder. It is too literal that for Kusama to be “anthropomorphic” is to be an object. Only here, instead of working with “hollowness,”(1) the question concerns the collapse of the inside and the outside: the projection of Kusama’s internal vision to her animatronic outside and the simultaneous containment of her from “the outside” symbolically or materially--whether it is within the establishment of the psychiatric hospital, the luxury brand, or the shop window.

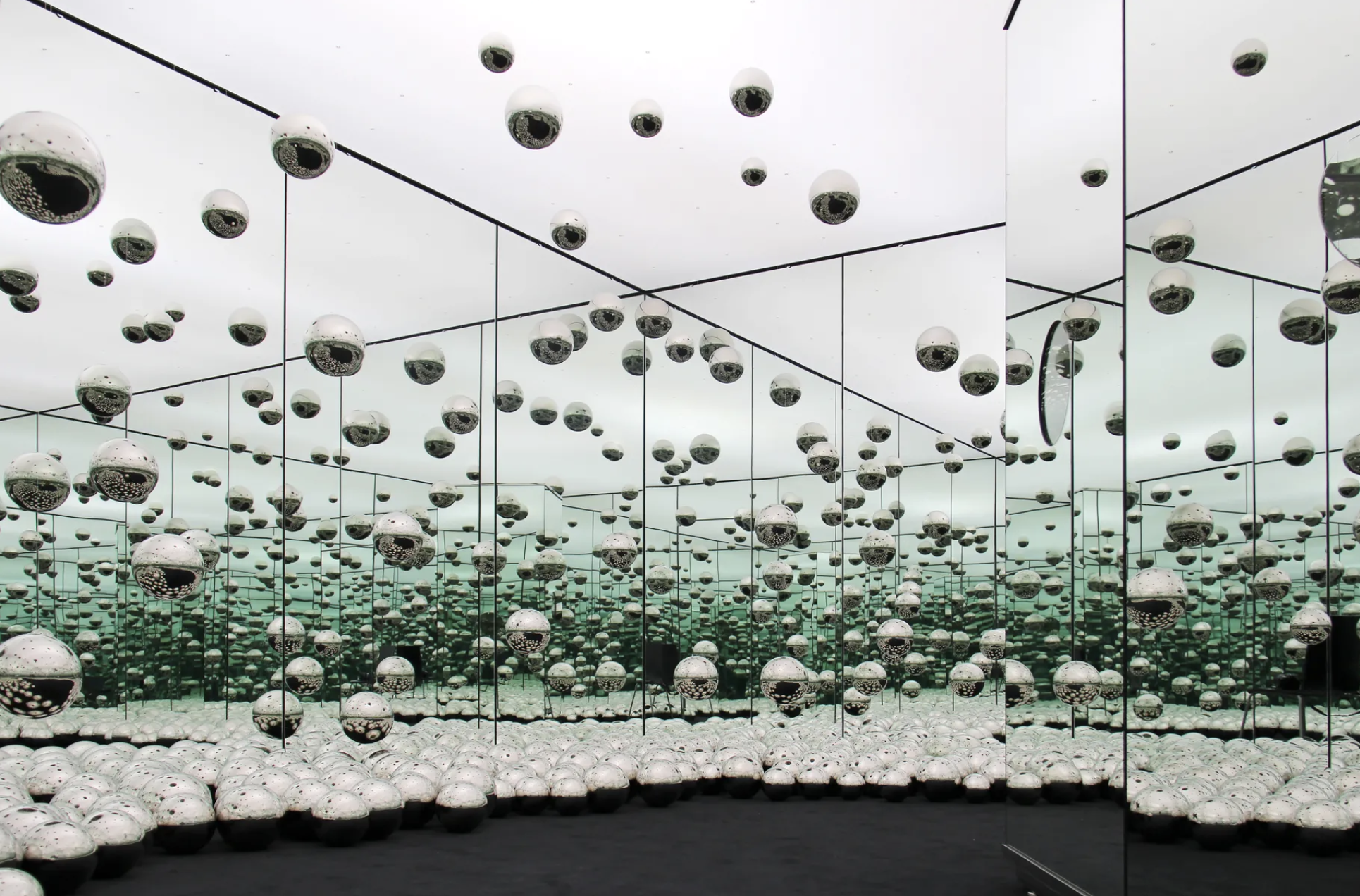

Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Room “Let’s Survive Forever”

This collapse of the artist and her double also underlines the theoretical defect in Fried’s critique, the conflation of anthropomorphism and objecthood: the assumption that being like a human is equivalent to being an object. The very fact that his theory works for Kusama, and that “she” is such a singular being, or object, casts doubt on the generality of the equation.

In the slippages of the animatronic and the anthropomorphic, what has kept me on my toes is that which remains undisclosed or curiously withheld in this condition of hyper-visibility, at the site of the body and the window:

What does it mean to live as an object? How to reenact the human stakes in the animated “thing”? Where do I stand? How does this “work” on display take possession of me– my consciousness and my body?

I find myself standing uncomfortably in a collusion of shame and pride: the pride of an Asian woman seeing an Asian woman artist’s elevation to the symbolic pinnacle of the world of consumption, and the shame to have to witness her fungible existence in the form of a ginormous inflatable crawling on top of a flagship store in the name of “sculpture”—at once on top of the world as we see it, and simultaneously encased by the reinforced erection of Asiatic female non-personhood.

Display of China: Through the Looking Glass (2015), Costume Institute Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the right, McQueen autumn/winter 2011–2012 collection.

“What follows then is not just a story about how we use people as things, or how things dictate our uses of them, but a drama involving a deeper, stranger, more intricate, and more ineffable fusion between thingness and personhood.”

-Anne Cheng

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks (1864). Courtesy of The John G. Johnson Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

A massive inflatable figure of Kusama looms over the Louis Vuitton flagship store in Paris

Image: Raphael Metivet

![]()

Image: Raphael Metivet

Anne Anlin Cheng in her critical proposition Ornamentalism, demonstrates the particular challenge that belies the non-personhood of the yellow woman. She attended to the McQueen porcelain dress exhibited at China: Through the Looking Glass. With a bodice made of porcelain shards, this unwearable dress evokes the corporeal gesture of the blue-and-white vessel and the ornamental ontology of the yellow woman– “we are looking at a peculiar form of anthropomorphism or prosopopoeia whereby the human is being used to recall objectness rather than vice versa.” The analogy to Kusama’s Vuitton work hardly needs pressing, yet the critique we need is not of commodification or fetishization, but to reiterate Cheng’s thesis: What is being at the interface of ontology and objectness?

Caught between the homogenization of space and the spatialization of difference, however, there is a particular danger to leaving bracket Kusama in a disempowered position, as appealing as that might be to our liberal sensibilities. The social media users who ironically called to “free Britney'', enjoying both their advocacy and imagined superior freedom, might think twice before calling us to “free Yayoi”. Kusama retains a massive social following and artistic ambitions, rewarded with viral commercial success. Not to turn a blind eye on the adversity she experienced in her earlier years, but her artistic complicity in the capitalist order of monetization/accumulation and expansion eludes any appeal to sympathize or critique this synthetic immortalization of an icon, and the reified eternalization of her vision.

If theater is not to be defeated, art is suspended. I feel kept on the other side of the looking glass, unable to look through. But I see the street, splattered with a sensibility almost metonymic to the dominant order of the world: one that is compulsory, replicable, endless, inexhaustive, infectious, homogenizing and dizzying. And yet full of holes.

1. Yet, the conditions of anthropomorphism need to be reviewed. Fried cites Donald Judd, a close friend of Kusama during her time in New York in the 60s, of his denunciation of the anthropomorphic tendencies in sculpture made part-by-part: “A beam thrusts; a piece of iron follows a gesture; together they form a naturalistic and anthropomorphic image. The space corresponds.”

This internal relational character risks the integrity of the work, which Judd seeks to resolve with singleness and indivisibility. But for Fried, Judd’s argument is immature in that the hollowness of some of his own work is intrinsically anthropomorphic, although latent. The shape found in Judd’s work creates (gestural) suggestion of an inside but contains the lack thereof. Many things are debatable here, but the conflation of anthropomorphism and objecthood strikes relevant. The conditions to be “like” human are not analogous to being “like” object, or the being of object.

special thanks to andrei pop for editing.