Dream Time

The Brooklyn Rail, Apr. 2024.

By Hindley Wang

UCCA Center For Contemporary Art

January 27–April 28, 2024

Beijing

Installation view of Dream Time, UCCA, Beijing. Featuring the works of Tirdad Hashemi and Soufia Erfanian (left), and Guanyu Xu’s photography on the right wall.

After three years of pandemic in China, the accumulated postponements finally succeeded in releasing the mainland’s art scene’s repressed libido and found ways to erupt at the tail of 2023 and rushing into 2024, the Year of the Dragon. The result was something like a celebratory malfunction (imagine 150 openings in a week). Yet it feels like everything is taking place on a gigantic petri dish: unrefined spots of uneven activities suspended over a shallow, uprooted ground—culture in development but under brutal exposures to state inspection. However, this enforced disclosure does not eradicate the possibilities for reactions beyond bureaucratic filters. In the 798 Art District—the legendary Beijing neighborhood that saw the rise of the Chinese art market and artists like Ai Weiwei in the 2000s—experimentation is still taking place.

Under the direction of Philip Tinari, the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) sits at the center of 798 and has now become the face of contemporary art museums in China. For context, UCCA’s track record shows an effort toward balance, with its main agenda roughly divided into three parts: staging institutional retrospectives for senior Chinese artists like Xu Bing, Cao Fei, and Liu Xiaodong; introducing household names “abroad” to the general public in China, such as Matthew Barney, Elizabeth Peyton, Luc Tuymans, William Kentridge, etc; with a third slice going to a mix of experimental endeavors focused on the native scene, in the shadow of the museum’s unhealthy appetite for the never-ending master series devoted to Picasso and Matisse.

What is taking place in Dream Time, UCCA’s inaugural show of 2024? For one, it cracks open the possibility for a new share of exhibitions in this seventeen-year-old institution, possibly setting a precedent for future thematic exhibitions enlisting international rosters. Curated by Fang Yan, Dream Time features fifteen artists and groups from all over the world, including many queer-identifying artists. The curatorial statement shares surprising affinity with the thematics of the Whitney Biennial 2024 over its contemplation of the real and issues of embodiment and identity.

The curatorial intention for physical movement in the space feels less burdened by the quest for transformation. Whereas its contemporary, the Shanghai Biennale’s Cosmos Cinema, with its robust program, can feel like an extraterrestrial invasion for the average local visitor, this one feels like a scattered landing from across different seas. A myriad of approaches to interiorities are put on view, each with accompanied strategies of disclosure, resulting in a concerted occupation of diverse, displaced voices. Take the works of the Berlin-based émigré artists Tirdad Hashemi and Soufia Erfanian. Neatly framed collaborative drawings are hung in a room painted deep blue. Each work is a collage of a larger pastel drawing of a flower, which embraces a window of a smaller drawing that depicts activities like dancing. The pictorial intimacy overlaps the interior affinities, sharing experiences of displacement and exile.

The rectangular cut on one of the ultramarine walls looks through to the photography of the Beijing-born, Chicago-based artist Guanyu Xu. Made in private homes of migrants in East Lansing, Hong Kong, and New York, the series “Resident Aliens” encapsulates three events of what the artist calls “temporal installation”: where personal photographs emblematic of the residents’ dreams and memories are printed out in various sizes and installed in the residence. Sticking on the edge of the doorframe or away from a mirror, the pictures within each work interface with and respond to their given interior, both physical and psychological. Xu captures the reflection, delusion, and illusion in each installation—distilling impermanent time in the marginal space that is precarious, foreign belonging.

The curatorial decision to make wallpapers out of Xu’s work as part of the display marks one of the many ways in which works become reachable to the audience, sensationalizing this space. But the compromise in such an approach is uncertain. The ambiguity that belies the distance between the space and one’s body persists.

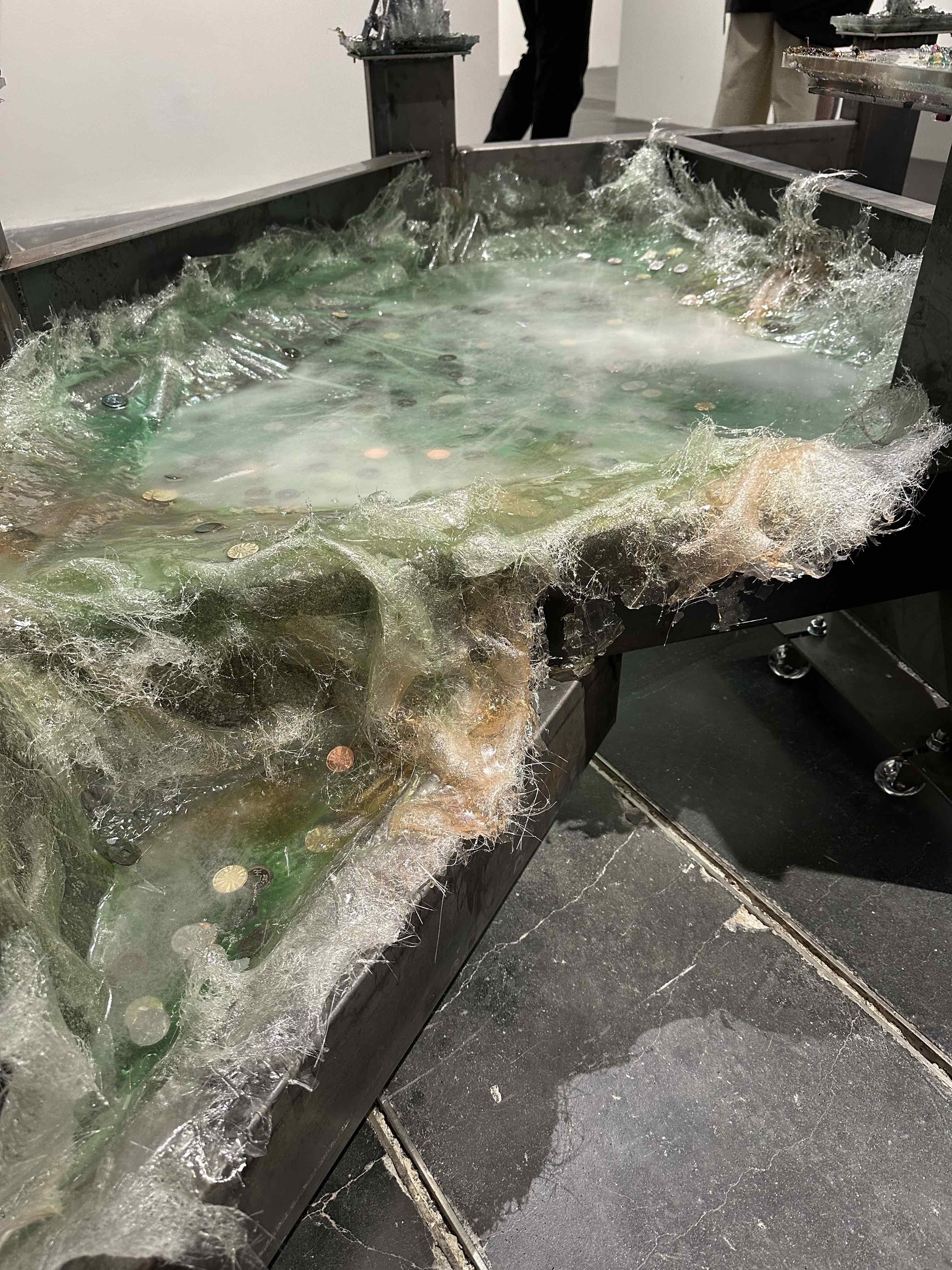

Stepping out of the first section, one enters an open space that is segmented with strategic placements of plaster walls, each occupied by at least one piece of wall-based sculpture or work. Feng Zhixuan’s Starwishenge (2023) anchors the room. Modeled as an archaic, interstellar wishing well, Starwishenge solidifies the changing matter in the unknown depth of the metal basins with hardened resin, marking the appearance of uncharted water within an intricate, empirical infrastructure of ecological and emotional energies. Its transparency, muted in the rusted green and blue matter, divulges evidence of passing and production: coins, Chinese medicinal elements, pearls, shells, and metal. This ritualistic reconfiguration of surplus and uncertainty is echoed in the adjacent long ink scrolls, by Aslı Çavuşoğlu & İnci Eviner. Titled Genies of Water (2023), the ink drawings document the disappearance of species lost to the pollution in the Turkish Ergene River—while reimagining mythical creatures from Anatolian cultures with ink extracted from the same polluted water.

Ma Qiusha’s Flowers in the Mirror (2023–24) looks like a life-sized cabinet of curiosities à la Domenico Remps (ca. 1689–1690s), and is filled with trinkets of Manchu princess dolls, ornamental flowers, miniature vases, antique treasures—authentic or fake, all kept in a precious display. This exhibitionist impulse invites voyeuristic desires to peek and loom, only to be confronted with the enveloping mystery that belies the objects’ similitudes in variety: many of them manufactured as exported goods now find their various ways “back” to their “origins.” What is lost is at sea.

The cabinet stands before the passage to the final section where one is led into the private zone for Peng Zuqiang’s hypnotics in Autocorrects (2023). Three panels are suspended in the dark room, words flashing in choreographed glimmers and subdued in the down-tempo beats, reminiscent of the nineties Mandopop: “My phone, autocorrects, I, into you, into me….” The scenes follow an unidentified person waiting, looking, and chasing, at airport terminals and train stations. The effect of the room feels like a familiar seduction that agrees with the body and its senses before consciousness can emerge from this affective amnesia.

This question of embodiment and identity in Dream Time culminates with Sin Wai Kin in the final room, with its walls transformed with flashy designs repeating the title of the work, It’s Always You (2021). The video plays on two TV screens in the center of the room next to a giant character cutout. In the video, four of Sin’s characters form a universal boyband, dancing in front of a green wall: one sexy, one playful, a serious one, and the aloof one. The four’s synchronized movements and uncanny personhood, in spite of their makeup, submerge the camera with assured desires and charm—insinuating a sense of unease in the viewer and consumer of this cabaret of solicitation. Sin’s specular fiction lays bare the formula of desirability and projection of fantasy capitalized in the entertainment industry. At the same time, it questions the desire for any stable imagination of the self, as the video chants at each singularly incongruous “you”: “I see my selves in you, reflected back at me.”

Dream Time is an answer to a collective psyche of enclosure. With this mélange, however, the search for critical iterations of agency inadvertently loses the plot as a collective under the protective privacy of a “dream.” Instead, this show seems to yield to a willful retreat and denial from “the real” (now vaguer than ever), substituting real issues with emotions, causes with symptoms—in a way an unacceptance amidst the tumultuous reordering of the signs and worlds in front of us. The works seem unaware of each other, even as they display a stylistic coherence in their cohabitation of this uncharted liminal space, which risks ending up more like a resolved comfort zone. But the unconscious is at work and on display, through spasms of loss and repossession slipping in windows of forgetful time and overlooked corners. A faint yearning for liberation is tinkered with the deluge of voices responding to influences whose origins are also left unidentified.