Elaine Cameron-Weir: A WAY OF LIFE

The Brooklyn Rail April Print

By Hindley Wang

Lisson Gallery

A WAY OF LIFE

March 7–April 13, 2024

New York

“We are each of us celebrating some funeral.”

—Charles Baudelaire, “On the Heroism of Modern Life,” 1846.

I had anticipated austerity before walking into Elaine Cameron-Weir’s first solo at Lisson Gallery, NY, but only to detect a kind that is strangely tinged with an impersonal sentimentality. In a sense of estranged memoriam, the archival aesthetics displayed in A WAY OF LIFE feels evocative of a Christian Boltanski room. Specifically, I thought of his Storage (1988) or Autel Lycée Chases (1989). However, instead of constructing a psychological landscape conjuring a particular historical affect, Cameron-Weir seems to be more interested in the phenomenon and the pattern, rather than effects or aftermath.

Known for her uncanny work on the mirror image and “Snake” series, begun in 2016—a found conveyor belt plated with individually enameled scales–Cameron-Weir retains the scale morphology by adorning a new rendition of a 500-inch belt with used horseshoes. western procession of my oldest wounds (hit parade) wrecked high altar of buying tears (2024) takes up the center gallery. Each horseshoe on the belt is unique, in its wear, dust, and tear.

Guarded by two sets of steel drums, the heavy metal belt stands upright with a straight spine, like a sloughing snake answering the charmer, its skins too heavy to feel alive. Each end is held up to delineate a giant U, forming the ultimate horseshoe. The artist has dealt us a familiar hand with her use of pulleys and pairs—her master trickery executing ideas and equilibriums that are too exact to be natural, but too cheeky to be allegorical.

However, the brutal, mechanical self-disclosure of the contraption betrays its instrument of hypnotics. The charmer’s buckets are full, and the lids uncovered. The enchantment is muted to an acoustic, vibrating in a distilled silence and scent—of oil candles burning in the lead basins in the buckets. Each drum face opens like a pit, the aftermath of a calculated explosion. Lead sheets are beaten to bear folds like tin foils, corners sprawling out of the bucket like unresolved menace, with edges shrinking from a halted spasm. The result is a mutation, disguised in solace. The muted drumbeats are imagined with steps paved with the scaling horseshoes, marching, and wailing.

Elaine Cameron-Weir

Snake 12, 2020

copper, enamel, stainless steel, sandbag168 x 16 x 60 inches

427 x 41 x 152 cm

Snake 12, 2020

copper, enamel, stainless steel, sandbag168 x 16 x 60 inches

427 x 41 x 152 cm

Our attention turns to find the subject of mourning on the other side of the room, where a crucifix cloaked in four leather jackets hangs. Titled pupil of couture / 4horsemen hairshirt (SS 2024 apocalypse collection) (2023), the two arms are perfectly leveled, its eight sleeves pulled up in a sacrificial gesture only for us to discover its improper weights: leathered and studded, with a crutch. This detail immediately shifts what used to be a display of tragic heroism to a sadistic submission. A nihilistic exhibition of heavy skins.

This deviation drives home the central quest: if we can hold all “variables” constant (symmetry, ideal double/other, ingenuity, individualism…), what becomes the slippage? Where lies the difference and how to constitute its existence? What is its attitude?

By way of the horseshoe, Cameron-Weir discovers a passage of return, precisely in the construction of the unnatural to make sense of the “natural.” This conceptual circuit reinforces the sense of stagnation and awkward tensions kept in symmetry in her installations. The works in the gallery’s second room appear less heavy or salient, perhaps because they are less dependent on suspension, with less room outside the artist’s control. A set of two identical sculptures sits still on the ground, each with a steel pallet base, the horseman jackets molded in lead lying flat on the curved track paved from two pieces of found construction waste. Oil candles burn in the troughs of the rusted cast iron pieces. The two names—dance macabre / waste management and stage makeup / vanitas (both 2024)—suggest the same sides of two coins, or two sides of the same coin: past life and still life, a pageant and a funeral.

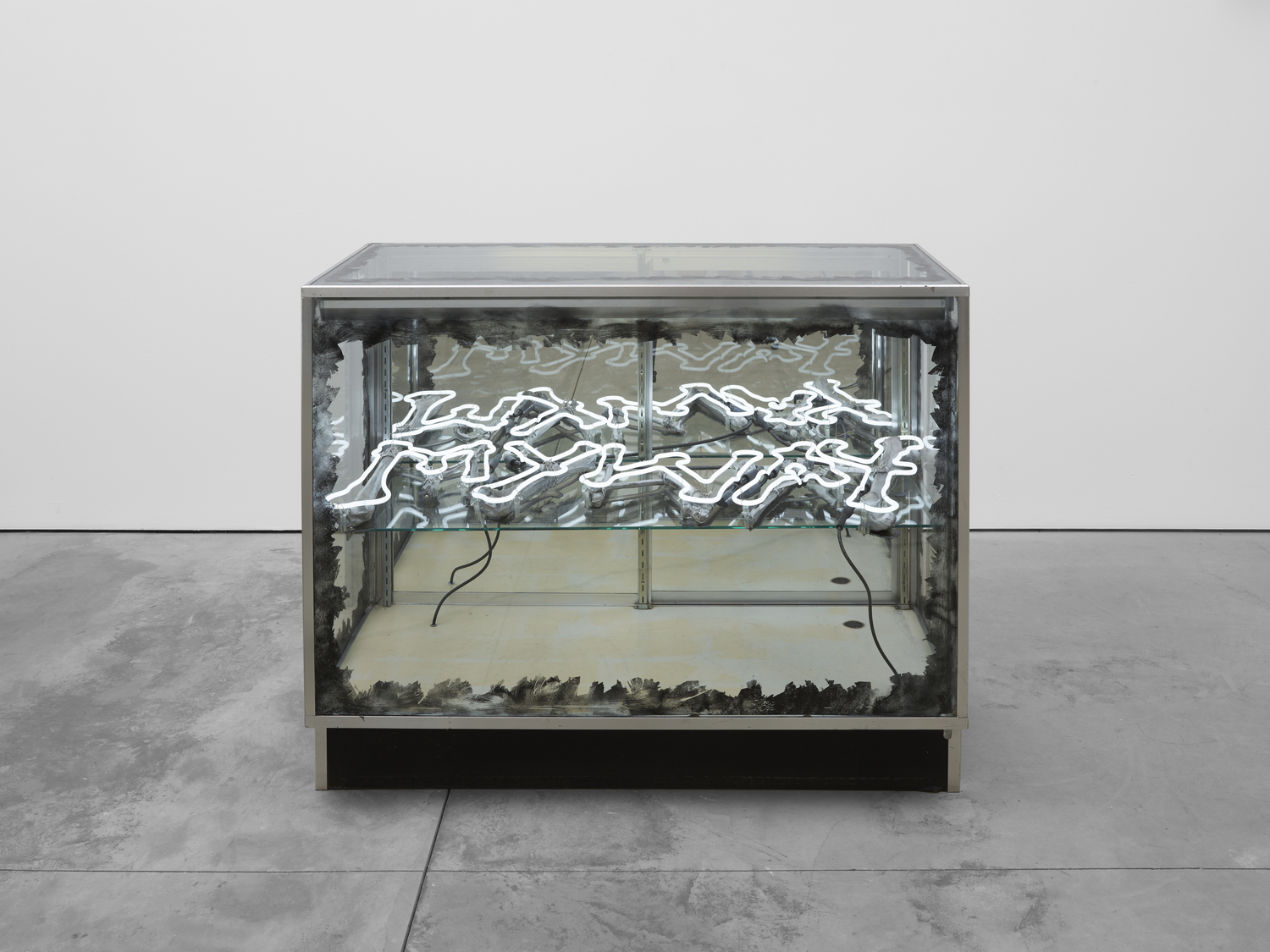

The artist’s proclivities for the unnatural also persist in the unruly edges of her works: the uneven outlines of the studded leather sandbags, the contours of the lead sheets coming off the rims of the steel drums, the magnetic micro-landscape attached to the used horseshoe nails on the frames of the identical mirror doors. A similar formal treatment is applied to the frames of the “marginalia” series (2024). Enclosed in white bronze frames with nails and their crinkled petals, arrays of enamel plates are linked through chains, each depicting a unique thorned barbed wire knot. Cameron-Weir etched each plate after one of the many patented designs developed during the late 1800s, describing a phenomenon of human ingenuity before the advent of standards and mass production. Defense entangles spikes, marking ways, signs of life.

There is no sentimental mourning for loss or erasure. To the end of days, Cameron-Weir is also indifferent. Behind the pursuit of symmetry and sameness, her work essentially concerns a metaphysics of repetition: no identical moment could pass twice. Through substitution and abuse, she follows and commemorates this impossibility to the depth of a laborious eternity. From the forgetfulness of each past, Cameron-Weir rediscovers, repurposes, and reconstructs what could respond to our new emotions in old exits—while excavating humor, greed, danger, and treasure.